Yitzhak Rabin

- Milestones

- Commemorative events

- Speeches

- Biography

- Archives

1941

1948

1949

1964

1967

1968

1974

1977

1992

1984

1922

1995

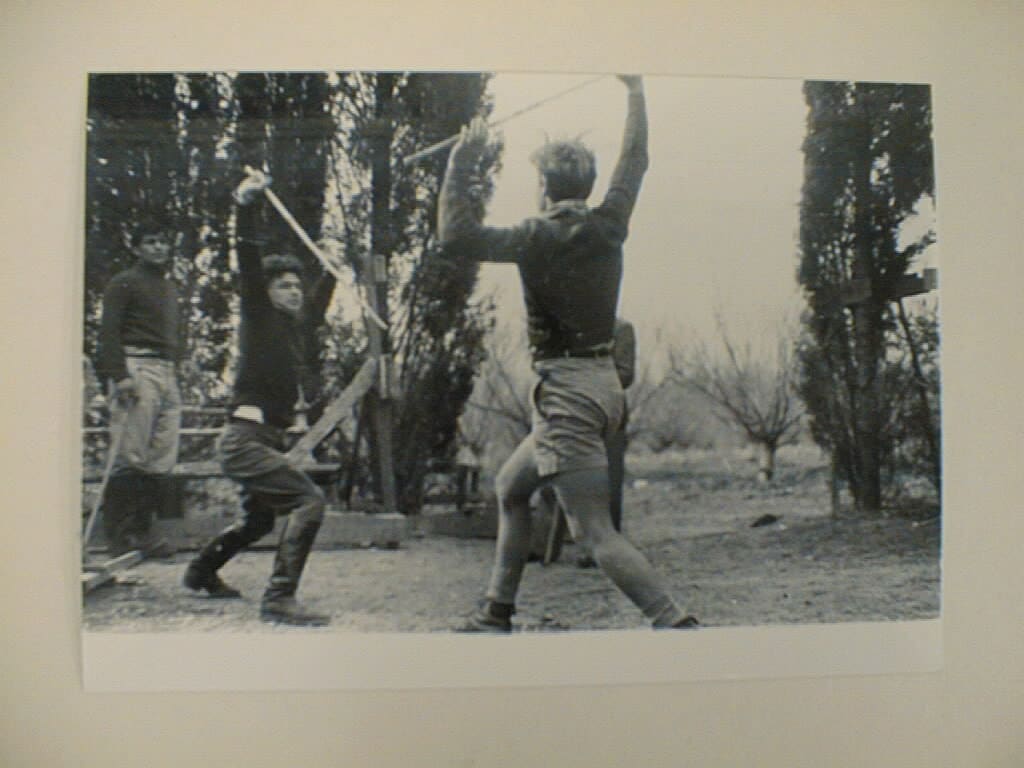

1941 – A Combatant and a Commander in the Palmach

In the summer of 1941, the Palmach was established, and Yitzhak Rabin was among the first to join its ranks. In 1943, several months after the defeat of the Germans in the Battle of El Alamein, the collaboration between the Haganah and the British army came to an end, and the Palmach needed to finance its activities by working at the kibbutzim. The new arrangement raised concerns in the Palmach lest they become idle, while those joining the British army would play an active role in the war against Hitler. Rabin was among those who stayed in the Palmach and considered the establishment of an independent Jewish force in the Land of Israel as the major task of his generation.

With the expansion of the Palmach and the organizing of military companies in battalions, Rabin was appointed Deputy Commander of the First Battalion.

At the end of World War II, the Yishuv leadership decided upon a new defense policy, which essentially posed a close fight for the achievement of the basic goals of Zionism – aliyah and settlement. In this context, the Haganah initiated the establishment of new settlements as well as illegal Aliyah. The conflict with the British was inevitable: many maapilim ships [illegally bringing refugees from Europe] making their way to the Land of Israel were unable to break through the British blockade. The maapilim, Shoah survivors, were removed from the ships and imprisoned at the Atlit Detention Camp. Rabin was the commander of the force that broke into Atlit in 1945, in the operation to release the maapilim, initiated by the Haganah. The operation was a success. During this operation, Rabin encountered Holocaust survivors, face to face for the first time.

In 1946, the Yishuv leadership decided to take the struggle against the British to the next level, and established the Jewish Resistance Movement, in which the Haganah, the Etzel, and the Lehi movements cooperated. After a series of activities, the British retaliated with a strong hand. On June 29, 1946, in a planned, comprehensive British military operation, preserved in the public memory under the name, Black Sabbath, the Yishuv leaders were arrested, and considerable weaponry was confiscated. Rabin was arrested with his father and sent for imprisonment from which he was released five months later. Immediately thereafter, he was appointed Commander of the Second Battalion of the Palmach. In October 1947, he was appointed as the Operations Officer of the Palmach.

“The Palmach, in its lifestyle, expressed a generation of volunteering sabras. A generation prepared to work to sustain itself. It expressed a type of new Israeli, a figure worthy of being a role model for young people. It was about the need for little to suffice and the same genuine, naïve willingness my friends and I had to sacrifice ourselves for the people.”

1948 – Independence

A Commander during the War of Independence

On November 29, 1947, the UN Assembly decided upon the partition of the Land of Israel/Palestine and the establishment of a Jewish state and an Arab state. The Jews accepted the proposal. The Arabs in Palestine rejected it and launched attacks on Jewish targets in an attempt to foil the plan. The War of Independence began.

As the Palmach Operations Officer and Liaison appointed to coordinate with the general staff, Rabin dealt primarily with reinforcing the Palmach troops with weaponry and human resources, as well as securing the route to Jerusalem, which was subject to incessant attacks from the Arab villages along the way.

At the beginning of April 1948, Yitzhak Rabin joined the Harel Forces, and within a short time was appointed as Commander of Harel Headquarters. He was in charge of alerting the defense line in place for the convoy transfer to Jerusalem and called for offense actions to be taken against the villages that were serving as bases for those attacking the convoys.

During the same month, the Harel Brigade was established and Rabin, at 24 years old, was appointed as its commander. Four days later, the decision was made to launch Operation Yevusi, intended to take control over Jerusalem immediately following the British evacuation. In the bitter battles within the city and the breakthrough into the city, dozens of his soldiers were killed. On May 14, 1948, the day the state was declared, Rabin was with his exhausted forces at the command post near Ma’ale HaHamisha.

On June 11, the first truce during the war went into effect. During the truce, the Burma Road, a bypass to Jerusalem was spurred open by the Harel Brigade, easing the siege on the city. Operation Danny began on July 9, to capture Lod and Ramla. Yitzhak Rabin served as the Operations Officer and Deputy to The Operation Commander, Yigal Allon. The sight of the convoys of displaced refugees with their belongings on their shoulders left a heavy impression on the IDF soldiers.

During the second truce, Palmach Headquarters was dismantled, amidst a tough debate, and its brigades were integrated into IDF units. Now, as part of the Israel Defense Forces, the Palmach prepared to capture the Negev.

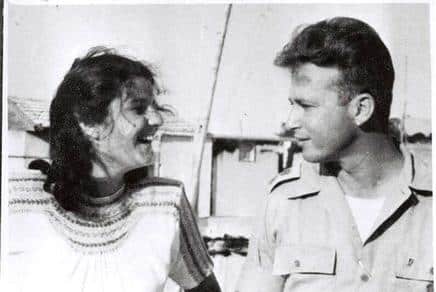

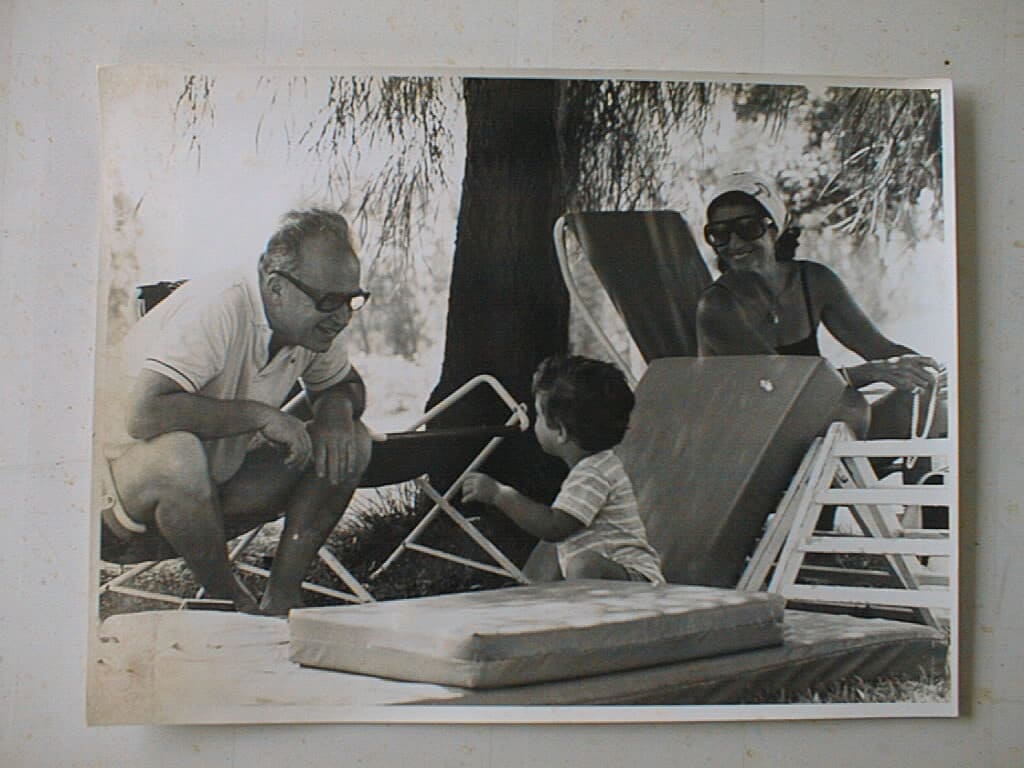

Rabin took advantage of the truce, and on July 19, he married his sweetheart, Leah Schlossberg.

Yigal Allon was appointed Commander of the Southern Front, and most of the members of the Palmach Headquarters joined him, including Rabin, who was appointed as Operations Officer of the Front and Deputy to Allon. In this position, Rabin dealt with planning major operations against the Egyptian army. During the battles, he was sent as Allon’s representative to ceasefire talks with Egypt in Rhodes. This was his first diplomatic task. In anticipation of

1949 – His IDF service

In November 1949, Yitzhak Rabin was appointed Commander of the School for Battalion Commanders. Many of the participants in the first Battalion Commanders course had served in the Palmach, and Rabin convinced them to continue to serve in command positions in the IDF, thereby preserving the spirit of the Palmach and its values. Rabin’s success in this position paved the way for his promotion in the IDF.

At the beginning of 1951, he was appointed Chief of Operations Department, a branch of the General Headquarters. During this period, he stood out as an outstanding figure, familiar with every detail in the many fields he handled, and he became a senior partner in the work of designing the IDF defense doctrine.

As a candidate for senior command positions, in November 1952, Rabin was sent to the Staff College of the British Royal Military Academy. In 1953, shortly after his return to Israel, he was appointed by the new Chief of Staff, Moshe Dayan, as Chief of the Training Department. In this position, he combined the experience he had gained in the Palmach and the British army, establishing the IDF training infrastructure. He was one of the founders of the Command and Staff School [known in Hebrew by its acronym, PoM], and he set new standards for educating commanders.

In 1956, he was appointed General Officer in Command of the Northern Command, and was responsible, among other things for fortification of Israeli control of the demilitarized territories between Israel and Syria, for protection of Israeli fishing freedom in the Sea of Galilee, and for defending the towns and settlements subject to shelling. During the Sinai Campaign, he remained in the north and prepared the forces under his command for the possibility of the opening of another front.

In January 1958, when Haim Laskov was nominated Chief of Staff and Tzvi Tzur as his deputy, Rabin felt that his promotion had been impeded, and planned to finally proceed with his studies, but that was not how things evolved. In April 1959, by mistake, the names of units called to participate in a military exercise were broadcasted on the radio. The announcement caused a public panic in Israel and an emergency military draft in Egypt and Syria. Following this blunder, which came to be known as “The Night of the Ducks,” the Chief of Operations was dismissed, and Rabin was appointed as his replacement.

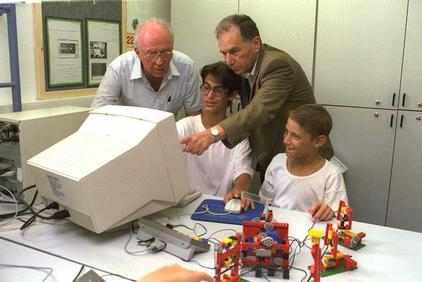

During his term as Chief of the Operations Department, Rabin dealt with consolidating a comprehensive IDF combat doctrine suited to developments in the Middle East arena and to technological development, while expanding sources for equipping the IDF and purchasing advanced weapon systems. Likewise, he took the lead in conducting multi-corps maneuvers. He was active in all areas of routine defense: on the northern front in the war over the water against Syria, and on the southern front against offensive initiatives by the Egyptian army. As part of his aim for rapid modernization of the IDF, the Computerization Department was established during his term, and the first computer was subsequently put into use by the IDF. At this time, he also promoted IDF relations with third world armies such as Ethiopia, Congo, and Iran.

In January 1961, with the appointment of Tzvi Tzur as Chief of Staff, Rabin was appointed, in addition to his position as Chief of Operations, as Deputy Chief of Staff. This appointment was a public expression of his senior status in the system and marked him as the next candidate for the position of Chief of Staff.

In June 1963, Levi Eshkol was elected Prime Minister, and in December of that year, the government approved the appointment of Rabin as Chief of Staff.

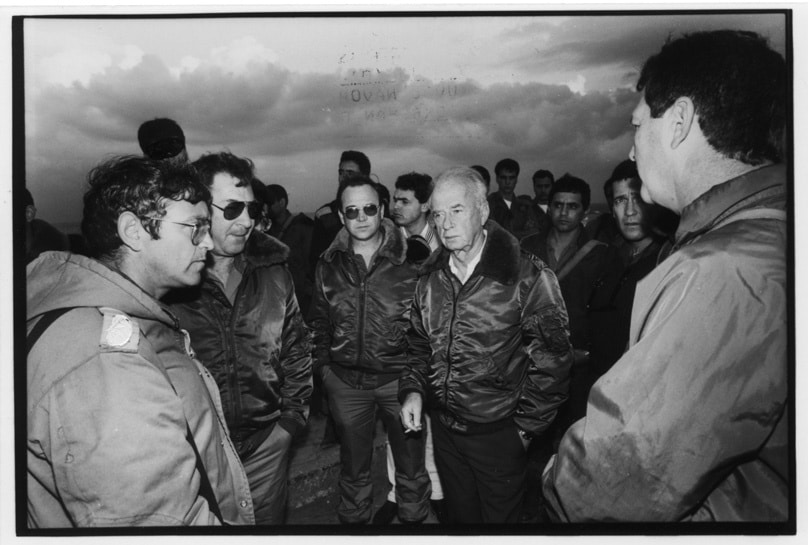

Rabin’s tenure as IDF Chief of Staff was marked by the rapid military growth of Arab states and their growing arsenal of Soviet weapons. His primary task was to prepare the IDF for the possibility of a total war. He engaged in equipping the IDF with innovative American weapons and technologies and training for coordinated, multi-force military action.At the same time, he worked diligently in preparing operational plans that would serve the IDF whenever and wherever necessary. All these withstood the challenge faced by the IDF in the days and months preceding its rapid and unprecedented victory during the Six-Day War.

One of the flash points was found in the Galilee, following attempts by Lebanon and Syria to divert the headwaters of the Jordan River flowing through Israeli territory. Rabin opposed any initiative that included occupying Syrian territory. He directed the IDF’s response toward disabling the mechanical equipment employed by the Syrians and their allies to divert the water.

Another campaign that Rabin was required to wage war against the Fatah, the military arm of the PLO, which was created in 1964. Since Fatah had established its bases in Syria and it was from there that the terrorists infiltrated for attacks in Israel, Rabin felt fully justified in acting against the Syrians. Rabin’s remarks in a press interview against the Syrian regime provoked a harsh response. They were later perceived as a factor that accelerated the preparations for war in Israel. In the face of attacks against the Israeli civilian population, Rabin was reluctant to order a response against the enemy’s civilian infrastructures. Nevertheless, in November 1966, he approved a reprisal against the Jordanian village of Samu’a, during which many Jordanians, soldiers, and civilians were killed.

At the end of 1966, after a three-year term as Chief of Staff, the Prime Minister decided to extend Rabin’s tenure another year.

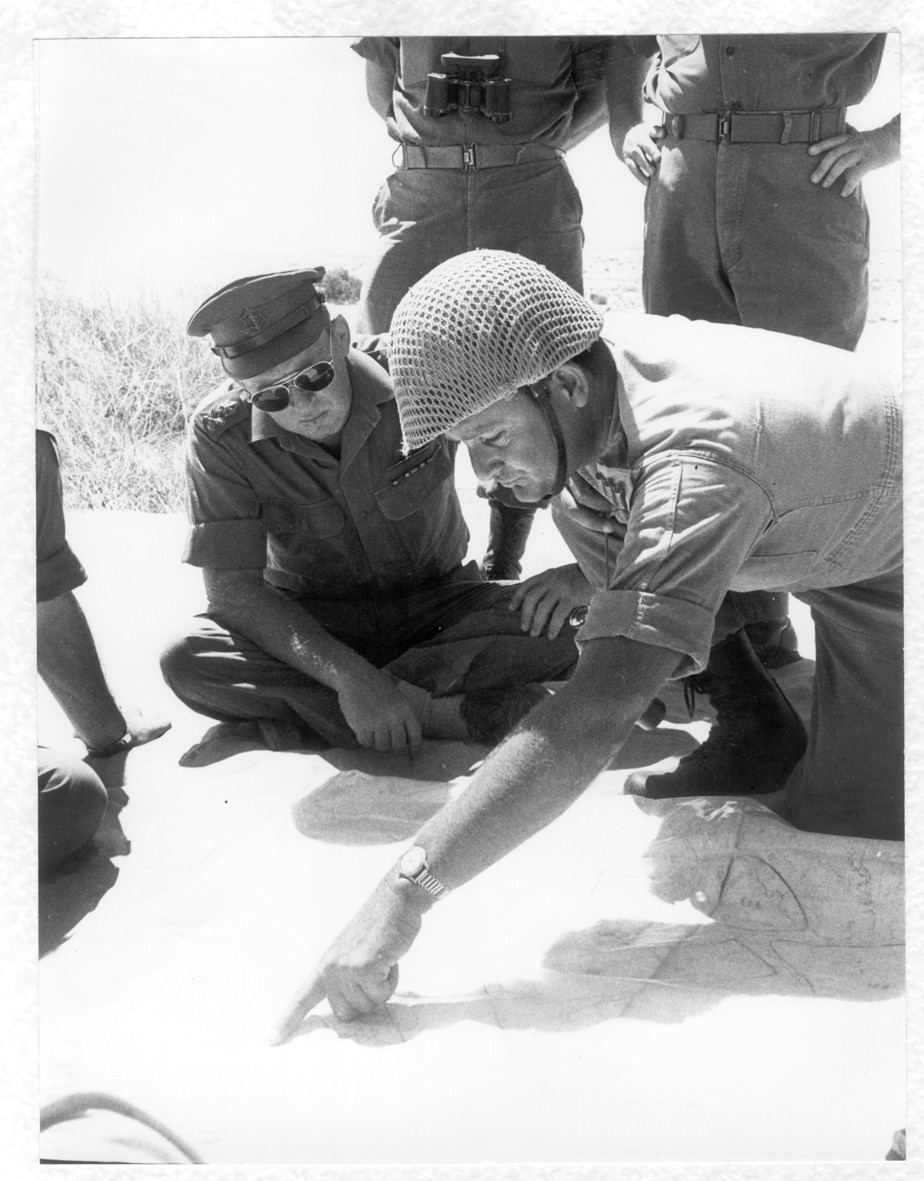

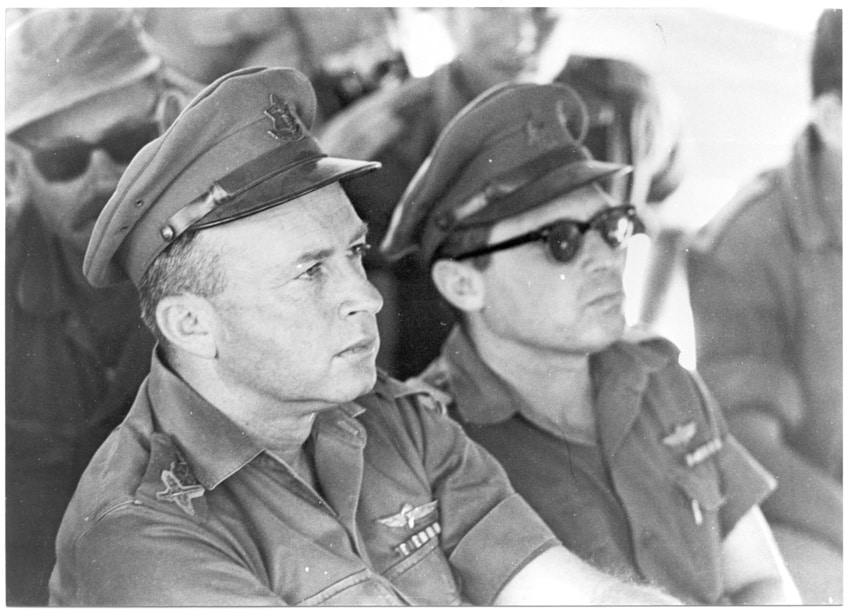

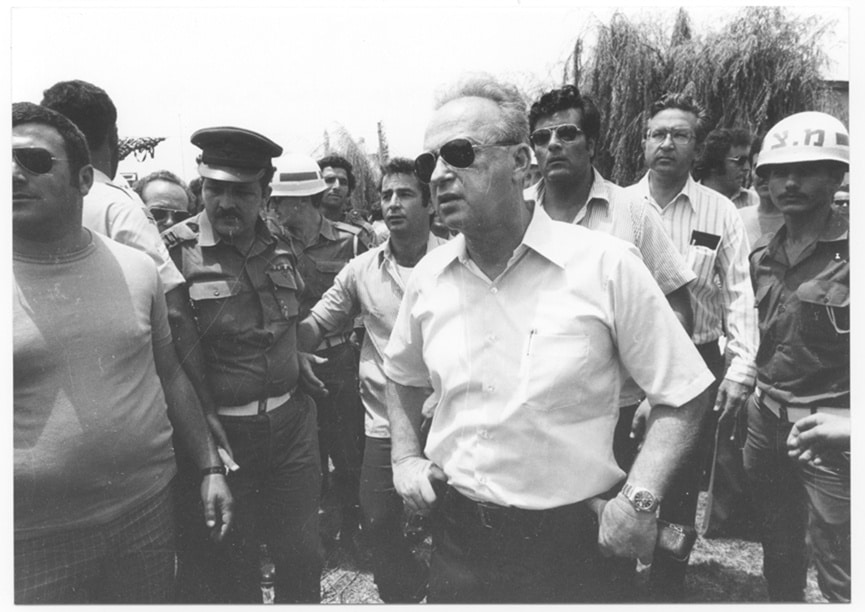

Photo: IDF and Defense System Archives, Avraham Vared

Photo: IDF and Defense System Archives, Avraham Vared

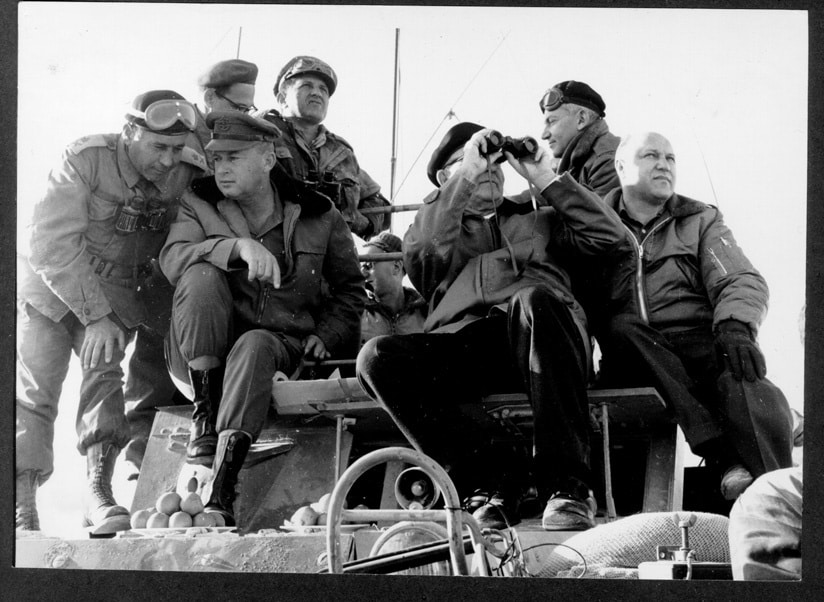

Photo: Archives of the IDF and the Defense System

Photo: Courtesy of Rachel Rabin-Yaakov

צילום: יוסף גבע

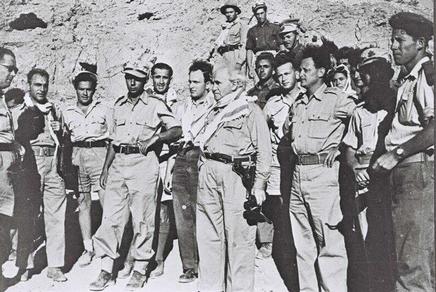

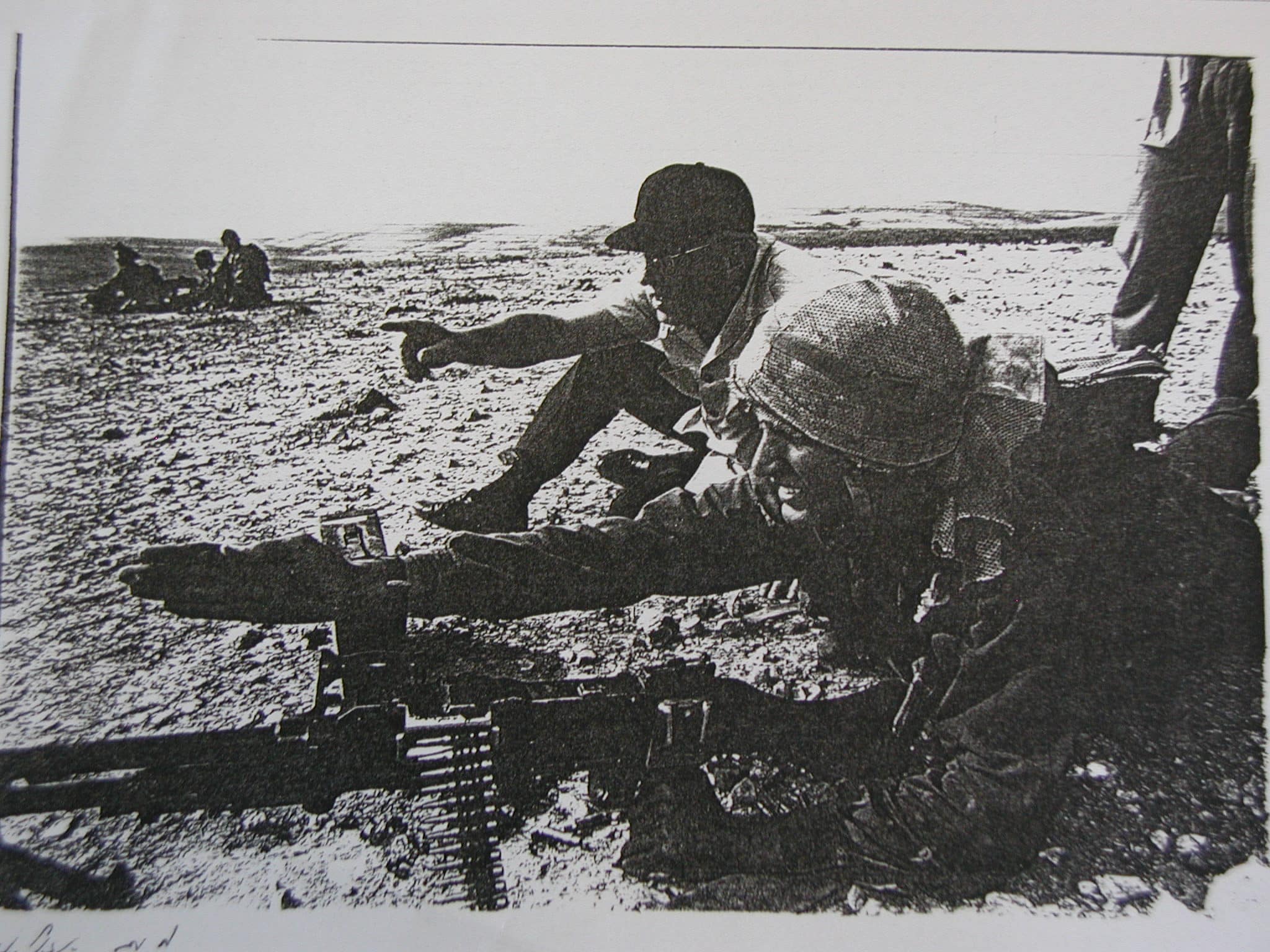

1967 – Chief of Staff, The Six-Day War

In 1967, in the fourth year of Rabin’s term as Chief of Staff, the Six-Day War broke out. At the beginning of the year, war had yet to become foreseeable to anyone, certainly not a war with Egypt. Ongoing clashes on the northern border were the focus of tensions. In response to Syrian activity, the Israeli Air Force took action, and in an air attack on April 7, six Syrian MiG aircraft were taken down. Egypt, which was allied with Syria by a defense pact, subsequently began recruiting its military reserve forces. The entry of Egyptian military forces in Sinai, in violation of agreements, was seen by Rabin as a belligerent move, and he recommended calling up the reserves. President of Egypt, Gamal Abdel Nasser, instructed the UN forces to leave Sinai, after which he closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli maritime traffic. On Israel’s part, this was understood as a declaration of war. The situation continued to deteriorate rapidly, and the war became inevitable.

Rabin was convinced of the power of the IDF to win, and that the army under his command was ready for battle. The price of recruiting the reserves was heavy. The public was anxious. The General Headquarters pressed for preemptive action. Nevertheless, Rabin understood that the government had to be given the time necessary for a diplomatic move. Senior figures with whom he consulted, shook his confidence in the power of the IDF to embark upon a war without the backing of a friendly superpower. Torn between his recognition of the need for landing a preemptive military blow and his recognition of his obligation to obey the political ranks, and while working around the clock and smoking incessantly, he was overcome by exhaustion and had difficulty fulfilling his role. Yet, after 24 hours of rest, he returned to the job.

The anxiety of the public during the “waiting period” resulted in the formation of a National Unity Government. Prime Minister and Minister of Defense, Levi Eshkol, was forced to relinquish his position as Minister of Defense, and Moshe Dayan was appointed to the job. On June 4, the government decided to launch an attack.

On June 5, with almost all the IDF fighter planes participating, the Israeli Air Force attacked the airports and the air forces of Egypt Syria, Iraq, and Jordan, dealing them fatal blows. After this crushing attack, the way was opened for the armored corps and the infantry to break into Sinai. The Egyptian army was defeated in just a few days and retreated to the Suez Canal. Following attacks by the Jordanian army in the Jerusalem area, another front was opened. Within two days, the IDF forces conquered the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and reached the Kotel – the Western Wall. Following the defeat of Egypt’s and Jordan’s armies, on the fifth day of the war, the IDF attacked the Syrians in the Golan Heights. After completing the task of conquering the Golan, the ceasefire went into effect and the threat over the northern towns and settlements was removed.

Rabin supervised the major attack by the Air Force from its headquarters. Once the results became clear, he moved to the so-called “pit,” the highest command post of the IDF. From there he followed the execution of the war plans and departed for tours in the various battle arenas. Except for a visit to Jerusalem after Israel took hold of the Kotel, he refrained from visits with media coverage and largely avoided being interviewed.

At the end of the war, Israel was a different place. The area under its control was three times what it had previously been, and responsibility for one and a half million Palestinians was placed on its soldiers. The controversy over the borders of the state which had ostensibly come to an end at the conclusion of the War of Independence was now reopened.

For his part in the victory, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem bestowed an honorary doctorate upon Lt. Gen. Yitzhak Rabin in acknowledgement of the appreciation felt by the Israeli public for the Chief of Staff of the victory.

In his speech, summarizing the war, he highlighted the heavy price of the war for the beaten and the victors alike, without either arrogance or victor’s jubilance.

“The combatants in the front lines saw with their own eyes not only the glory of victory, but its price. Their friends fell by their sides wallowing in their blood. And I know that the awful price that the enemy paid also touched the depth of the hearts of many of them.”

SIX DAY WAR. DEFENSE MINISTER MOSHE DAYAN (C), CHIEF OF STAFF YITZHAK RABIN (R) AND JERUSALEM COMMANDER UZINARKIS ENTER THROUGH THE LION'S GATE INTO THE OLD CITY.

1968 – Ambassador of Israel to the United States

At the beginning of 1968, following 27 years of military service, Yitzhak Rabin was honorably discharged from the army and appointed to his first civilian position: Ambassador of Israel to the United States. His first year in office coincided with the US presidential election. Rabin took advantage of this to learn the mechanisms of American government, as he became acquainted with the prominent media personalities in the US, and developed relations with the Jewish communities and heads of the leading Jewish organizations.

Contrary to the tradition of Jewish support for the Democratic Party, Rabin openly supported Richard Nixon, the Republican candidate for president. A prior acquaintance between them, and tracking his positions during the election campaign, reinforced Rabin’s estimation that Nixon would be the better ally for Israel. Nixon’s victory and the nomination of Henry Kissinger as Head of the National Security Council created the conditions for Rabin’s great achievements as ambassador. Despite the tremendous tension at this time between Israel and the United States, surrounding US government plans for arrangements in the Middle East to which Israel objected, Rabin managed to cultivate special relations between the two nations. His efforts on behalf of the agreement of Golda’s government to the ceasefire in the Suez Canal contributed to cancellation of the American embargo on the shipment of Phantom jets to Israel.

In September 1970, Nixon asked Israel, via Rabin, to assist King Hussein of Jordan to foil Syrian and Palestinian attempts to threaten his rule. Rabin supported the request and acted to convince the prime minister to honor it, even at the price of war with Syria. Hussein succeeded, ultimately, to suppress the revolt on his own, but the willingness of Israel to help substantially strengthened cooperation between Israel and the United States, increased American economic assistance for Israel, and improved the king’s relations with Israel.

Golda, like her predecessor, Levi Eshkol, regarded Rabin as an ambassador with special status, and opened a direct channel of communication with him.

In the second half of his term, Rabin consolidated his status as a diplomat and as a candidate for senior political roles in Israel. He learned to appreciate American democracy and the accomplishments of its free economy. His connections with the government leaders and the Jewish communities expanded and he became highly esteemed.

The death of the President of Egypt, Gamal Abdel Nasser, in 1970, and the election of Anwar Sadat changed the political reality in the Middle East. The American government saw this as a window of opportunity for promoting arrangements between Israel and its neighbors and intensified its actions to reach interim agreements. Rabin supported the idea of promoting peace in stages and was aware of the hidden potential in Sadat’s offers of an agreement with Israel. He believed that the withdrawal of the IDF from deep in the Sinai desert and the opening of the Suez Canal would open the way to an arrangement with Egypt, which would also reinforce the alliance with the United States. He warned the Israeli government that its refusal to accept the American plan would result in an imposed agreement if not renewed eruption of war. But Golda’s government stuck to its positions.

The election campaign for the eighth Knesset was imminent, and Rabin expressed his interest in returning to Israel.

In March 1973, after a five-year term as ambassador, Rabin returned to Israel and joined the Labor Party. In anticipation of the elections in December, the party’s “Electoral List Committee” assigned him to the 20th place on the party list headed by Golda Meir. About a month and a half before the upcoming elections, it turned out that Israeli was not facing elections, but war.

Taking Israel by surprise, the Yom Kippur War broke out on October 6, 1973. For the first time in years, Rabin held no position or authority. His attempts to attach himself to this or that commander failed. On the fourth day of the war, he accepted the offer of Minister of Finance, Pinchas Sapir, to head an “Emergency Support Drive,” to raise funds for the war expenses.

In the elections held in December, immediately following the war, the Labor Party’s power was diminished, yet, it still managed to put a government coalition together. Rabin was appointed as Minister of Labor in Golda’s second government. On April 2, 1974, the Agranat Commission published its report of inquiry into the failures of the Yom Kippur War. The Commission refrained from discussing the performance of the political ranks and placed the blame on the military ranks only. Rabin publicly took exception to the decision to place the responsibility for the failure in its entirety on the shoulders of Chief of Staff David Elazar.

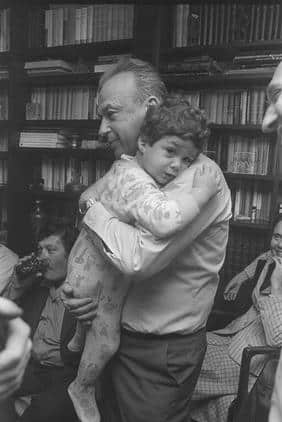

Public opinion was ill at ease with the conclusions of the report. Demonstrations that started with just a few participants became progressively larger and a call was heard for judgement to be passed regarding the political ranks. Under the pressure of the events, Prime Minister Golda Meir resigned, and the Labor Party was required to appoint her replacement. Rabin was a surprising candidate for this senior position, but he was clean of involvement in the failures of the war and enjoyed support from a distinguished group of veteran Labor Party members resulting in his being pushed forward, over the other candidates. He was nominated by the party to fill the place of Golda Meir as prime minister.

“I was convinced that the value of our relations with the United States and with Jewry in the strongest country in the western world would become progressively stronger.”

1974 – Prime Minister of Israel, first term

First term as Prime Minister of Israel

Rabin assumed the position of Prime Minister on June 3, 1974. During the three years of his term, he promoted policy representing the continuity of Labor Party leadership of the government, yet also changes in personalities at the helm and party willingness to accept changes.

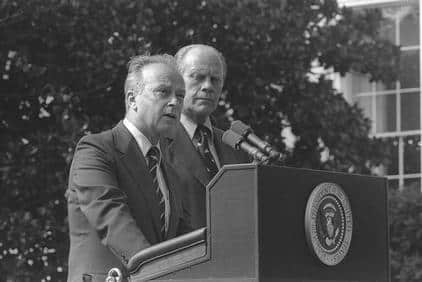

He considered the renewal of the diplomatic initiative and progress towards peace as an imperative and opened negotiations with Egypt on an interim agreement through mediation by the US Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger. The agreement, one of his outstanding achievements as Prime Minister, was reached after tough and intense negotiations, filled with crises, and signed on September 1, 1975. Eventually, Rabin saw this as the first piece of the full peace agreement with Egypt that was signed four years later by the Likud government under the leadership of Menachem Begin. Following the signature on the agreement, a Memorandum of Understanding was reached with the American government under President Gerald Ford, by which the United States assumed far-reaching commitments for the security of Israel and its economy.

In the framework of Rabin’s attempts to promote communications with neighboring states, he held clandestine meetings with King Hussein and the first covert visit by an Israeli Prime Minister with the King of Morocco.

While working towards peace, Rabin had to cope with acts of terror by the PLO against Israeli citizens. He objected to any negotiations with the PLO and argued that the Palestinian problem could be solved in the framework of relations with Jordan. He adopted a harsh and uncompromising policy towards Palestinians supporting the PLO.

In the second year of his term, Gush Emunim established its first settlement, Sebastia, in Samaria. Rabin opposed Jewish settlement in centers of Arab population yet refrained from harsh confrontation with the settlers. After some hesitation, he approved the establishment of the Jewish settlement in Kadum. Thus, the way was paved for the ongoing settlement which he opposed.

On March 30, 1976, Land Day took place in the Galilee with the Arabs there demonstrating against the confiscation of their lands. During the turbulent demonstrations, the security forces responded with live fire and six demonstrators were killed. The event evoked harsh reactions from the Arab public, as well as among the Jewish public, and this convinced Rabin that the relations of the state with the Arab minority required reconsideration.

Throughout the period of his term, economic growth continued, the social security network was preserved, and the gaps in society were reduced. These successes were appreciated by the public. The Entebbe Operation to release the prisoners taken from the Air France plane raised his status throughout the world, but incidents of corruption among his party’s leading figures and the residue from the Yom Kippur War connected to them, placed a dark shadow over the accomplishments of his government and enraged many in opposition.

On December 10, 1976, the first F-15 planes from the United States arrived in Israel. Their landing after the beginning of the Sabbath resulted in a government crisis with the religious parties. Hoping that early elections would lead to increasing the power of his party, Rabin submitted his resignation to the president on December 21. From that point and until the election of the new Knesset, Rabin’s government operated as a transitional government.

Amidst the election campaign, it was discovered that his wife had a bank account in the United States, which at the time was not legal. After she was brought to trial, Rabin decided after his three-year term, to resign. Shimon Peres was appointed to replace him.

Rabin’s decision to share the responsibility for his wife’s violation of the law drew tremendous public admiration.

“I can no longer be the party candidate for prime minister. Not because of the severity of the crime… but because I violated the law, even if only technically, and I must act according to my education, my tradition, my personal code of behavior – and pay the price. So it is for any citizen, all the more for the Prime Minister seeking the faith of the people for another term.”

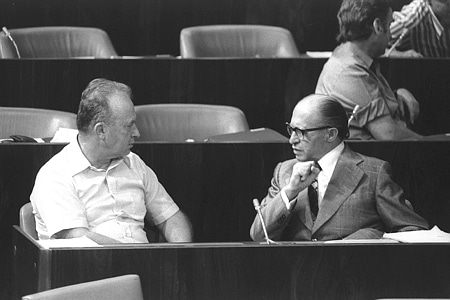

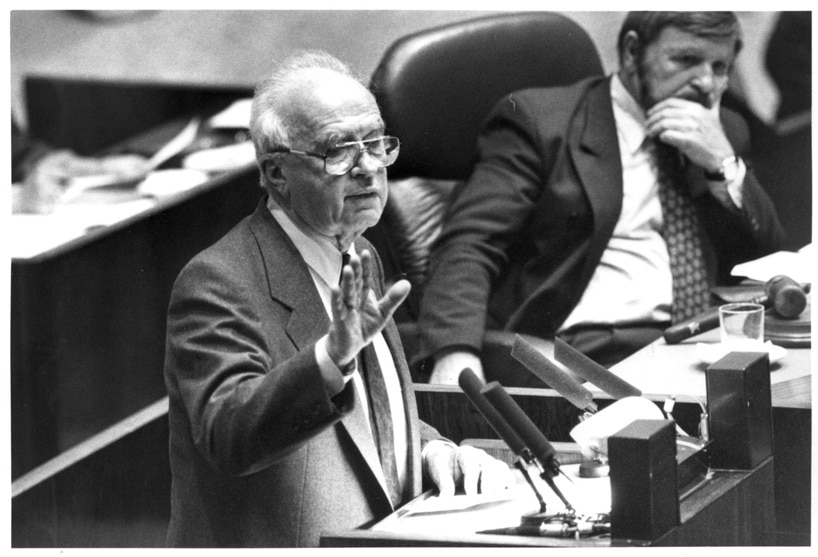

1977 – In the Opposition

In the Knesset elections held on May 17, the Labor Party lost its power, and for the first time the Likud led by Menachem Begin, put together a government. The Labor Party moved to the Opposition. As a member of Knesset, Rabin enthusiastically accompanied Sadat’s visit to Israel. Despite his reservations regarding clauses related to taking down the settlements in Sinai, he supported the peace agreement with Egypt in the Knesset.

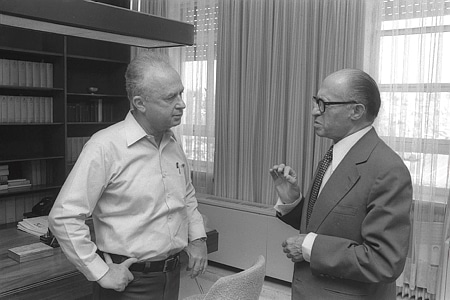

In 1979, he published his book, “The Rabin Memoirs,” in which he summarized his military path, and he laid out his accounts with his political opponents, particularly with Shimon Peres. In his little office in the Kirya in Tel Aviv, allocated for his use as a former prime minister, he spent much time writing to newspapers, meeting with old friends, and breathing life into the camp of his supporters in the party.

For the elections held in 1981, in the Labor Party, he supported Yigal Allon as the party candidate for prime minister. Yet following Allon’s sudden death in February 1980, he announced his candidacy. Peres was nominated by the party, but the Likud won the elections.

On June 6, 1982, Operation Peace for Galilee, the First Lebanon War, began, to protect the towns and residential settlements in the north. Rabin supported the early stages, but as the war went on and its goals were extended, he warned of the sunset of the IDF in the Lebanese mud, and he demanded the withdrawal of the military forces to a security strip from which they could defend the northern border of Israel.

“Opposition is a very important institution in a democratic state, and certainly in ours. If you don’t have a choice, you have to sit in the Opposition and do the work.”

1992 – Rabin, Prime Minister of Israel, Second Term

Israel is Waiting for Rabin

As a citizen, a rank-and-file member of Knesset, severed from the decision-making hub, Rabin followed the Gulf War which changed the balance of power in the Middle East. The reaction of the Israeli home front during the war sharpened his sense that the Israeli public was tired of wars and would be willing to pay the price of peace. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the core of anti-Israeli activity in the region, he saw a historic opportunity for progress towards peace. In the agreement reached between the superpowers at the Madrid Conference in October 1991, he saw the reinforcement of this trend. He believed that under the new circumstances, a window of opportunity was created for peace, and that it must be used to its fullest, quickly, before nuclear weapons reach the region and endanger the very existence of the state.

The Wave of Aliyah – immigration from the Soviet Union – and its intrinsic economic potential for the state reinforced his acknowledgement that Israel could now take risks. He knew brave leadership was needed for that purpose, and he believed it was within his power to fill the role. Following his victory over Shimon Peres in the Labor Party primaries, the party launched an intensive election campaign. Enjoying his status as a credible persona, “Mr. Defense” aiming for peace, widely embraced by public faith, Rabin led the election campaign under the slogan, “Israel is Waiting for Rabin.”

“We are amidst a period of danger that unconventional weapons will enter the Middle East… Therefore, looking at seven to ten years, we must advance a diplomatic process.”

Prime Minister Again

The turnover that returned the Labor Party to the government returned Rabin to the seat of the prime minister. He kept his promises and changed the national priorities: budgets for education, welfare, infrastructure, periphery towns, and Arab society grew significantly at the expense of the budget for settlements and defense. Guarantees from the United States for absorbing the olim [immigrants] from the former Soviet Union made it easier to carry out his plans and breathed life into the state economy. He earned affinity from the business sector by his support for a policy of market privatization.

Determined to integrate Israel quickly into the age of world reconciliation and lead a brave diplomatic step towards peace with the neighboring states and a solution to the Palestinian problem, he announced he would be willing to make territorial concessions. He immediately renewed peace talks with the Palestinians and with Syria that had begun after the Madrid Conference. He saw the Palestinian problem as the heart of the conflict, however, when it became clear that the talks in Washington with the representatives from the Occupied Territories had reached a dead end, he promoted the Syrian track, hoping that by their very existence, it would accelerate progress along the Palestinian channel as well.

His defense policy moved along two parallel tracks: while relieving sanctions over the lives of the population, he continued with a tough policy towards acts of terror and violators of the public order. It was an unusual step when he decided to deport 415 members of Hamas who were involved in terrorist attacks. Operation Accountability came in response to Katyushas fired in the north.

When he was updated on confidential peace talks in Oslo, he approved their continuation despite his doubts and made them the official channel of communication. He approved the PLO joining the talks as a party to the agreement only after a letter of commitment from Yasser Arafat affirming PLO recognition of the State of Israel and its departure from the ways of terrorism.

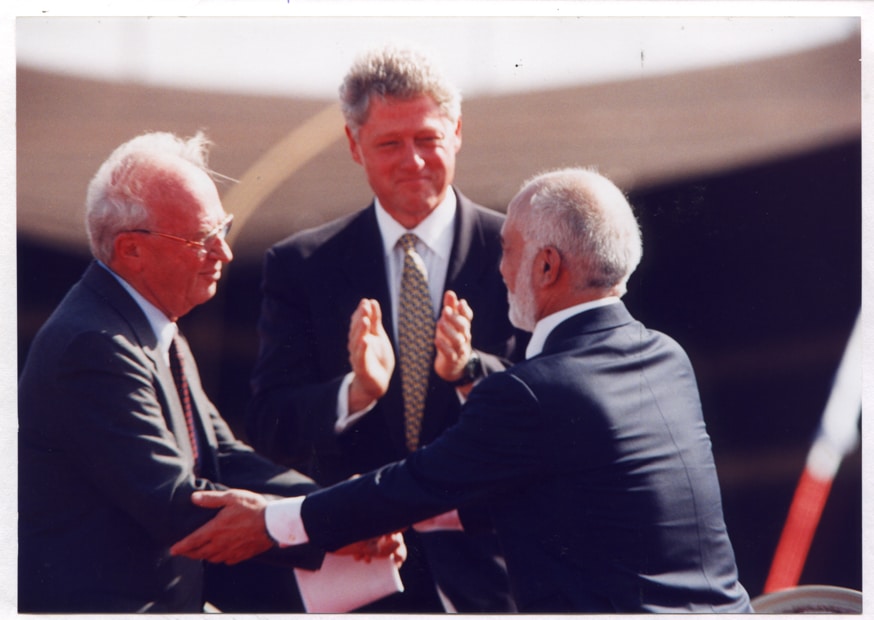

On September 13, 1993, in a festive event on the lawn of the White House, in the presence of the President of the United States, Bill Clinton, the Oslo Accords were signed. The agreement laid the foundations for a permanent arrangement which would include the establishment of a Palestinian national entity alongside Israel. The speeches by Rabin and Arafat and the historic handshake between them were the climax of the ceremony and became a symbol of hope in Israel and the world. Together with joy and uplifted spirits, the agreement also aroused fears of potential dangers and intensified the controversy between the supporters of this move and its objectors. The settlers led political and public protest of the agreement. The massacre of Muslims praying at the Cave of the Machpelah in Hebron by an extremist Israeli reflected the rising tension in Israeli society. Rabin considered dismantling the Judean and Samarian settlement, but in the end, left it in place.

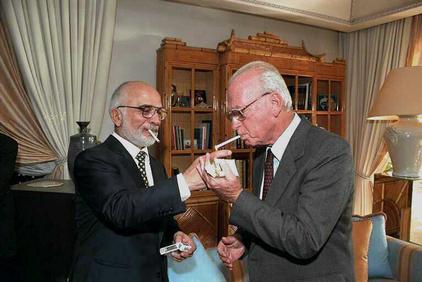

Peace Agreement with Jordan

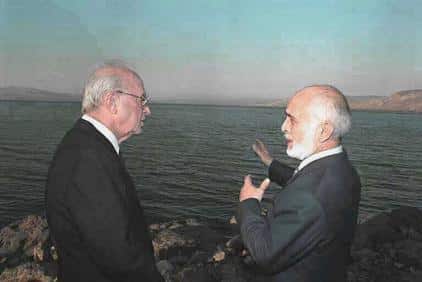

Upon the signing of the Gaza-Jericho agreement, and recognition of the Palestinians as a national entity, conditions for a peace agreement with Jordan ripened. Relations with the Jordanian Kingdom were built over long years of confidential contact between King Hussein and Israeli leaders, including Rabin. In May 1994, a decisive, confidential meeting was held between Rabin and Hussein, and the foundations for the peace agreement were laid. The generous aid that the United States promised to Jordan gave the final push towards this step. On October 26, 1994, the peace agreement was signed in the Arava and the borders between the two countries were finally set. This agreement was an important stage towards ties with other Arab and Muslim countries.

Repeated and recurrent suicide attacks by Palestinian objectors to the agreement that hurt innocent civilians in Israel’s big urban centers severely damaged the hope that a new age of prosperity had emerged for the entire region.

“Not only nations are making a pact of peace with one another today, not only our peoples are shaking hands for peace here in the Arava. You and I are making our peace here, peace of soldiers, peace of friends.”

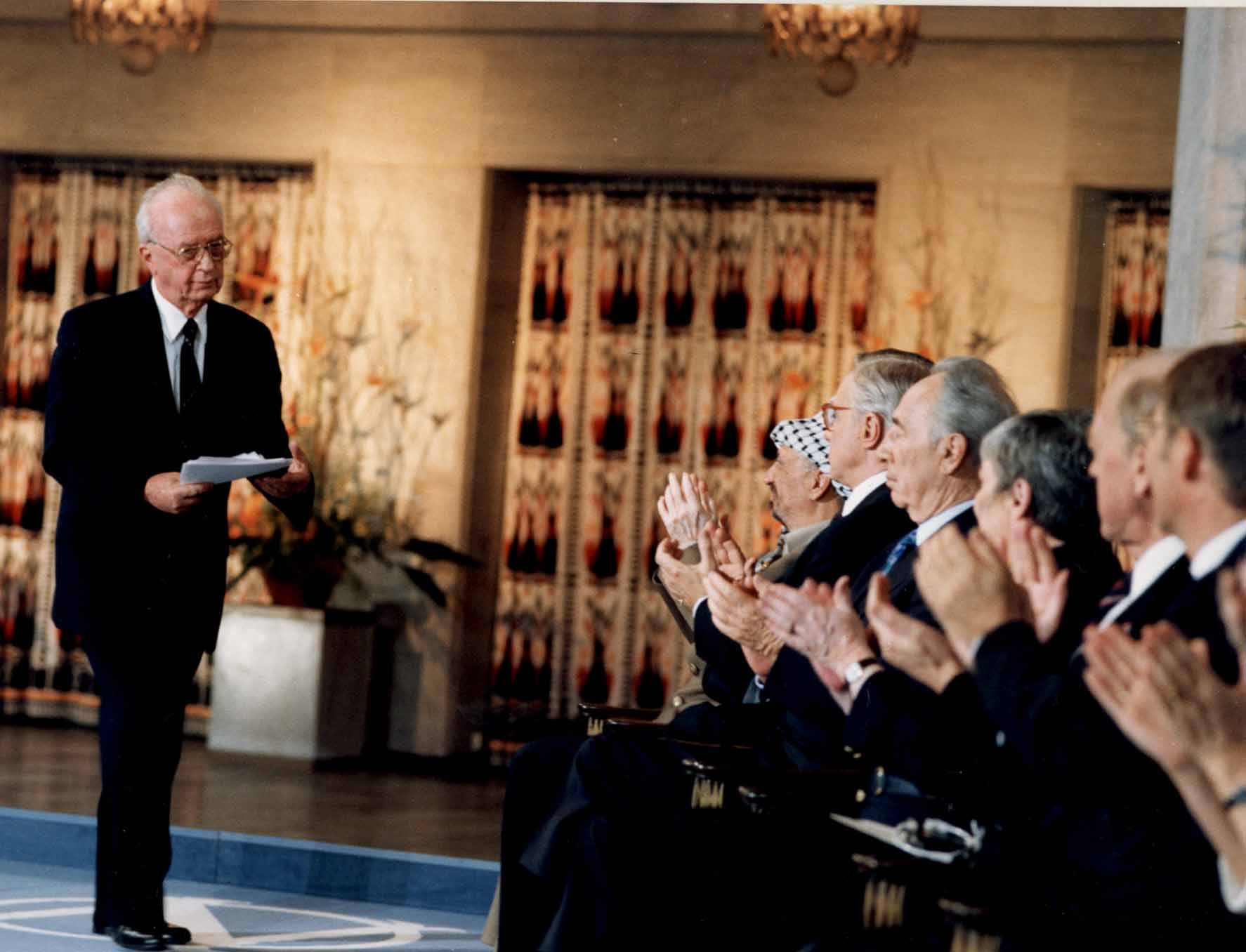

The Second Oslo Agreement

Receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in December 1994, symbolized the admiration and respect from the nations of the world for the breakthrough on the road to peace, and it was an expression of encouragement and hope that they would progress on their path and complete this difficult step.

However, the mood among the Israeli public was different. Renewal of peace talks with Syria created a new camp of objectors that rejected any concessions in the Golan. The terrorist attacks continued and even intensified, and the split in Israel society widened, but Rabin was determined to continue.

In September 1995, an agreement was reached regarding a time schedule for implementation of the Oslo Accords and ways for implementing it. It was signed in Washington and popularly called “The Second Oslo Accords.” The opposition to the agreement organized to impede its execution. They arranged demonstrations and protests of the agreement and the mind behind it, Rabin. Incitement was heard from the demonstrators, interpreted by extremists as justification for letting blood.

“Peace, you make with enemies.”

Photography: Yossi Roth

Photo: Yaakov Sa'ar, Government Press Office

Photo: Zvika Israeli, Government Press Office

Photo: Avi Ohion, Government Press Office

Photo: Avi Ohion, Government Press Office

Photo: Avi Ohion, Government Press Office

Photo: Yaakov Sa'ar, Government Press Office

Photo: Meir Azoulai, Yedioth Ahronoth

Photo: Israel Sun Ltd

Photography: Yitzhak Harari

Photography: Yitzhak Harari

צילום: לשכת העיתונות הממשלתית

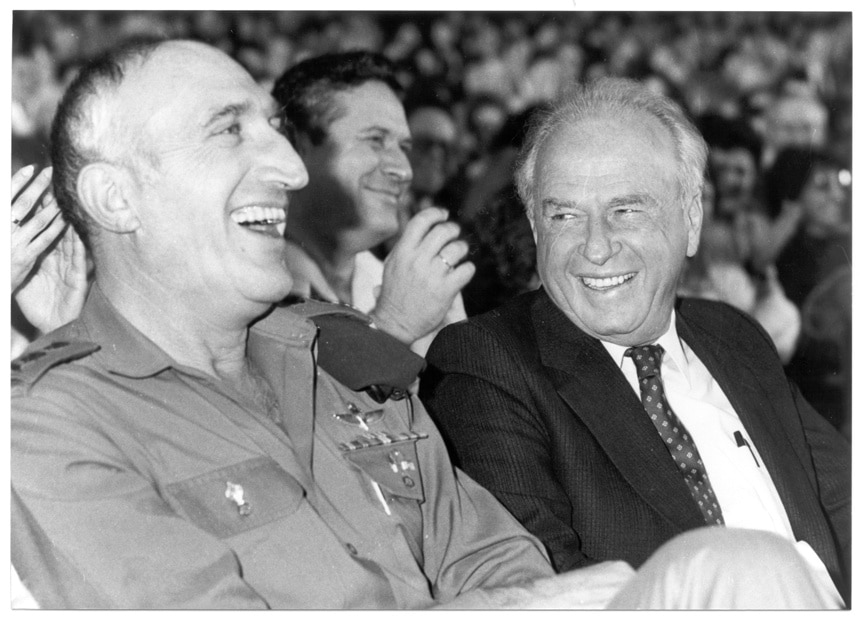

1984 – Minister of Defense

After the elections held on July 23, 1984, neither of the big parties had enough seats to put together a government, and a national unity government was established. According to the agreement between the Likud and the Labor Party, Shimon Peres served as Prime Minister first and at the end of two years he handed the role over to Yitzhak Shamir.

Peres appointed Rabin as Minister of Defense, and he was reelected for the job by Shamir until the end of the term of the third unity government led by Shamir in 1990.

During his term, he worked to take the IDF out of Lebanon in stages and solidify the IDF hold on the security strip. Unlike all his predecessors, he agreed to a cut in the defense budget, a step which was made possible after Egypt departed from the cycle of warfare. His consent to the Jibril Deal, the release of 1,150 Palestinian prisoners in exchange for three Israeli prisoners generated a public debate, but the responsibility for the lives of Israeli prisoners tilted the scales for the approval of the deal.

When the Intifada erupted, he did not recognize its unique character at first. In the first few months, he believed there was a military solution to the uprising by the people, and he acted accordingly to suppress it by force. His policy appeared unethical and purposeless in the eyes of the left, and insufficient in the eyes of the right.

After several months of conflict, he became convinced that the uprising was an expression of authentic Palestinian nationalist yearnings which Israel could no longer ignore. The willingness of the Palestinians to absorb losses surprised him and led to recognition that the policy of force alone would not restore the quiet. He was aware of the growth of a local Palestinian leadership, and for the first time saw it as a partner for diplomatic negotiations. Amidst this, he had growing concerns regarding the implications of the Intifada for the combat spirit of the IDF and its status as a people’s army.

In 1989, he formulated a two-stage peace initiative in the context of which he proposed allowing elections for local leadership in the occupied territories, which would manage the Palestinian autonomy regarding which agreement had been reached at Camp David, and this would ensure that things would remain quiet in the territories. In the second stage, according to the initiative, negotiations would be conducted with the elected leadership regarding a permanent arrangement. Under American pressure, the plan gained the support of Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir. In 1990, the unity government fell apart, and the Labor Party returned to the Opposition.

“It is easier to solve a military problem. It is harder to solve a problem that touches 1.4 million people – a civilian population that doesn’t want to be under our authority.”

Photo: Archives of the IDF and the Defense Establishment, Mickey Tzarfati

Photo: Yuval Navon

Photo: Natan Alpert, Government Press Office

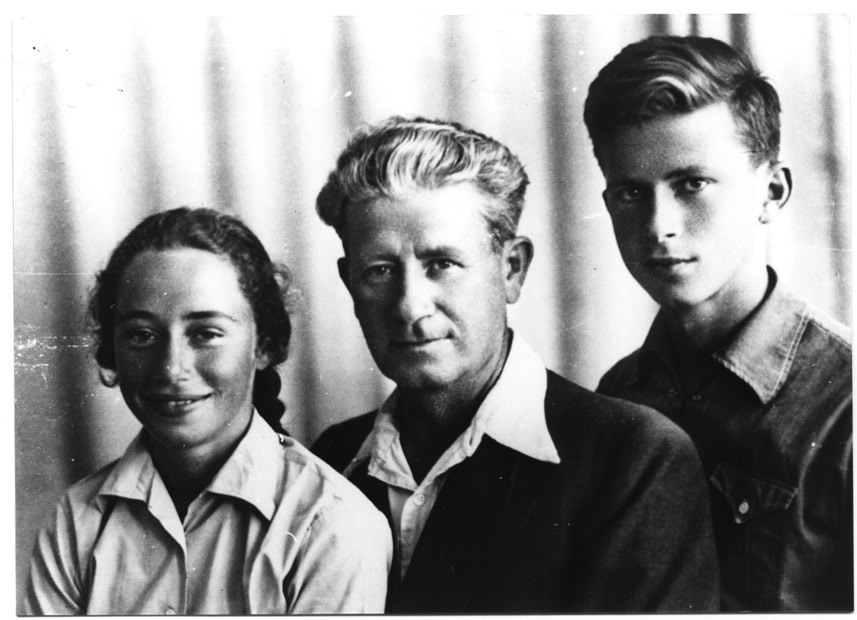

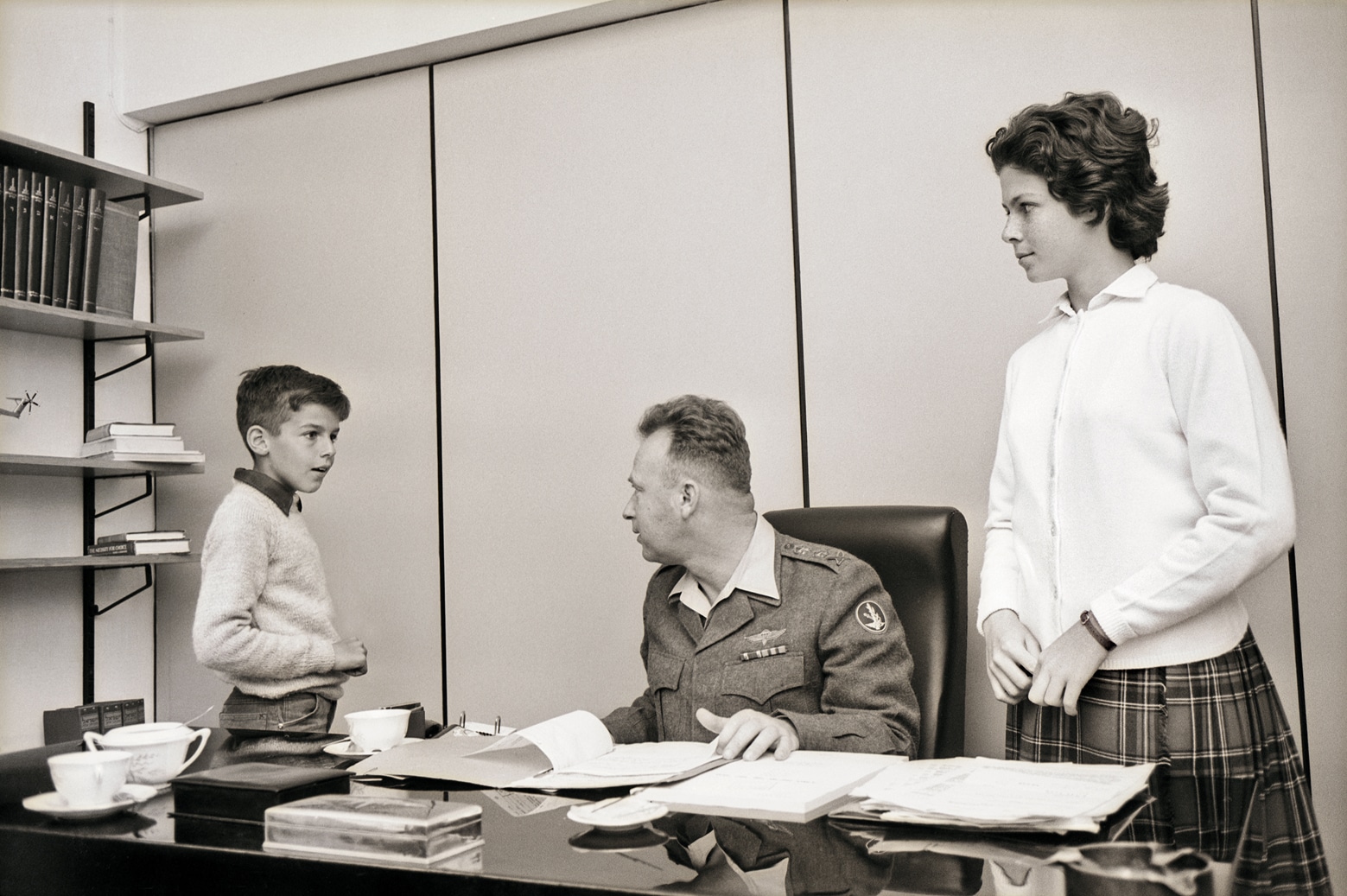

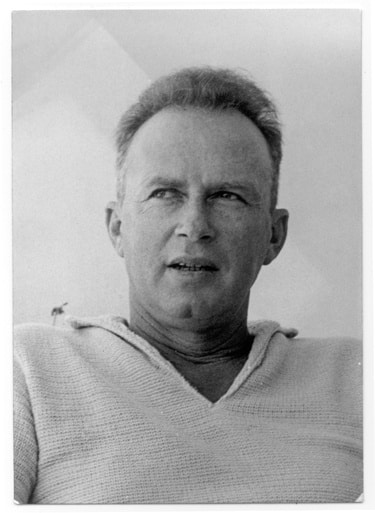

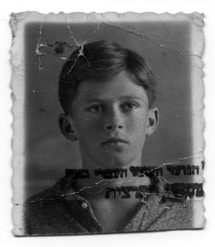

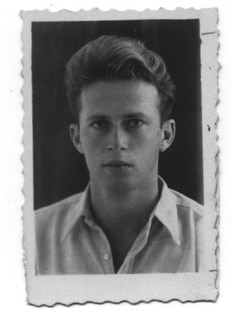

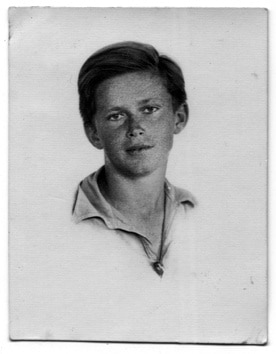

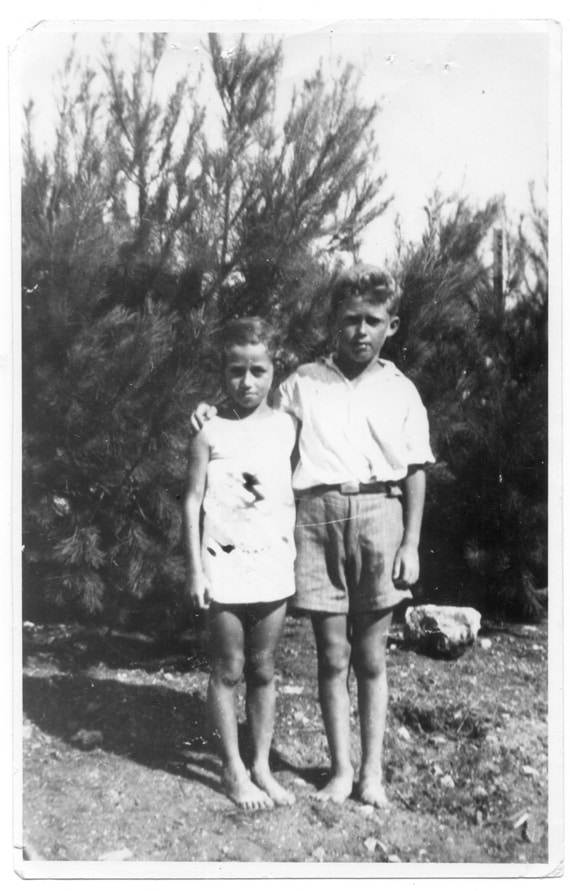

1922 – Childhood and Family

Yitzhak Rabin was born on March 1, 1922, in Jerusalem. His parents, Rosa Cohen and Nehemiah Rabin, were among the pioneers of the Third Aliyah. Nehemiah worked for the electric company and Rosa worked as a bookkeeper, but most of their energy was invested in volunteer public activity. Rosa held senior positions in the Haganah [paramilitary organization during the British Mandate period], in the Tel Aviv municipality, in the Histadrut [Labor Federation], and in the education system. She was known by the handle Red Rosa in the Yishuv. Nehemiah held positions in the Haganah and in the Histadrut.

In 1923, the family moved to Tel Aviv, where Rabin spent his childhood. His sister, Rachel, was born in Tel Aviv in 1925. When he was 15, his mother died from an illness.

In his parents’ home, Rabin absorbed values that guided him throughout his life.

“It was during my childhood that I formulated a sense of responsibility for the position, a love of the landscape and the Land of Israel, a sense of camaraderie.”

School Years

In 1928, Rabin began his studies at Beit Hinuch for Workers’ Children in Tel Aviv, the school which became his second home. It set the goal for him to design and form the world of the tzabar, the Israeli sabra, the new Jew, connected to the landscapes of Israel, working the land, defending it from antagonists, and shaped his willingness to be recruited for any task. The emphasis was placed on combining studies with work, field trips, and social activity.

The activity in the HaNoar HaOved youth movement was an inseparable part of the life of the schoolchildren. In that framework, Rabin was exposed to the doctrine of Jewish socialists, and trained for hagshamah – self-actualization – at a kibbutz.

Agricultural studies were the natural continuation of his education at Beit Hinuch. Rabin studied at the District Agricultural School at Givat HaShlosha for two years. Then, in 1937 he reached his coveted target, Kadoorie Agricultural High School at Kfar Tabor, where many of the best youth from the working settlement got their education. At Kadoorie, Rabin became acquainted with Yigal Allon, who recruited him to the Haganah, and the ties of friendship were formed between them. The school was known for its high level in theoretical studies and the special lifestyle that evolved among its students and teachers. Rabin’s talents rapidly stood out. The certificate of excellence that he received upon completing his studies paved the way to higher education for him. However, when World War II broke out, and the concerns about its implications for the reality in the Land of Israel ensued, he forfeited his plans and joined Kibbutz Ramat Yohanan.

In May 1941, he was called to participate in a military operation in Lebanon intended to help the British army. This was his first trial by fire.

“At an age when loves blossom, at age sixteen, I was given a rifle to protect my life – and most regrettably, to kill in a moment of danger… I thought a hydraulic engineer was an important profession in the barren Middle East… but I was compelled to hold a rifle.”

Photo: Courtesy of Rachel Rabin-Yaakov

Photo: Courtesy of Rachel Rabin-Yaakov

Photo: Courtesy of Rachel Rabin-Yaakov

Photo: Courtesy of Rachel Rabin-Yaakov

Photo: Courtesy of Rachel Rabin-Yaakov

1995 – Assassination of the Prime Minister of Israel, Yitzhak Rabin

Shalom Haver, Farewell Friend

The peace process supporters’ camp that accompanied the progress in the talks with hope was shocked by the magnitude of public objection and decided to provide a stage for the wide public support for the steps the government was taking.

A demonstration organized for November 4, 1995, drew masses of people to the city square, Kikar Malchei Yisrael, in Tel Aviv. Demonstrators expressed their support for the agreements and for Rabin’s leadership. Although Rabin was not initially enthused by the idea of a rally for support, he conceded to the organizers’ invitation and agreed to deliver remarks from the stage. Among the applauding masses, for a moment he felt his public supporters were multitudinous. At the end of the rally, while returning to his car, a Jewish assassin shot three bullets in his back.

The Prime Minister of Israel, Yitzhak Rabin, was assassinated.

On Saturday night, November 4, 1995, on the Hebrew date of 12 Heshvan 5756, Yitzhak Rabin arrived at Kikar Malchei Yisrael in Tel Aviv to take part in a mass rally under the slogan, “Yes to Peace – No to Violence.”

At the conclusion of the warm and supportive rally where masses demonstrated their faith in him and their love for him, Yitzhak Rabin was shot on his way to his car and fatally injured by a Jewish assassin.

Yitzhak Rabin died at Ichilov Hospital at 11:14 P.M., after all efforts to save him by the doctors were unsuccessful.

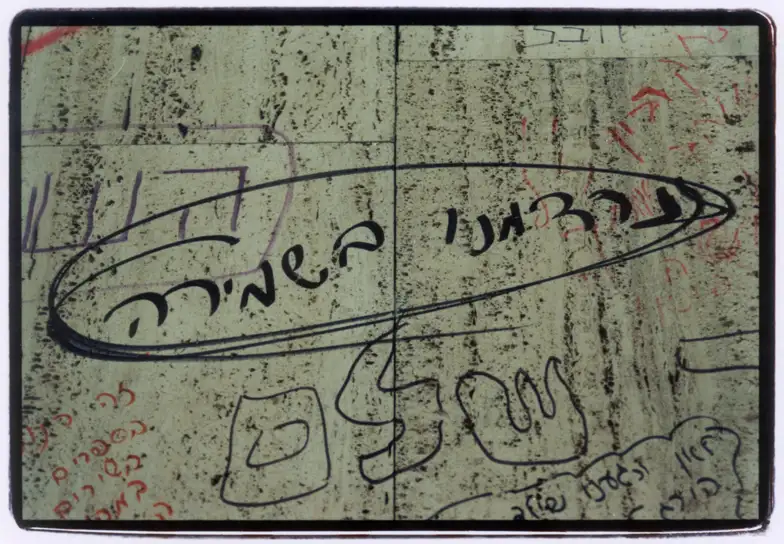

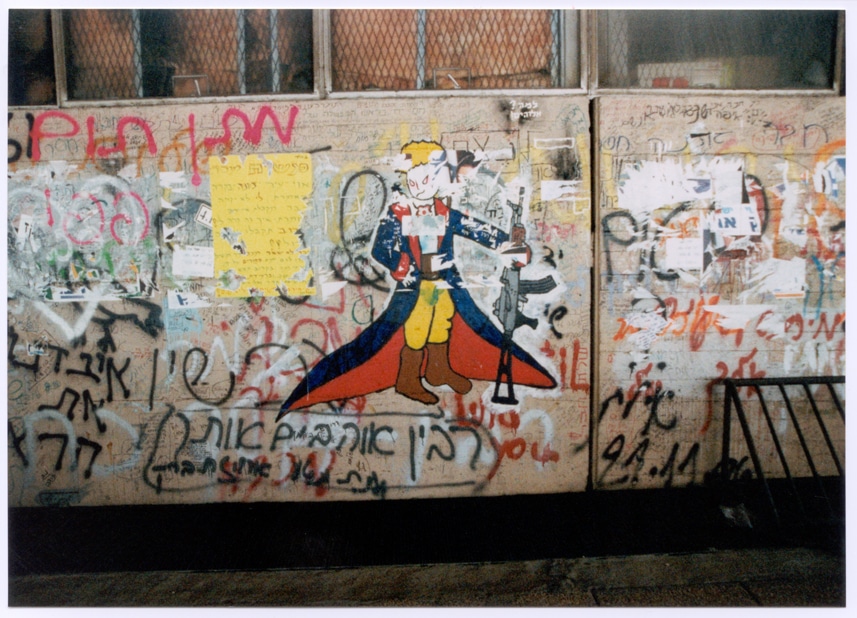

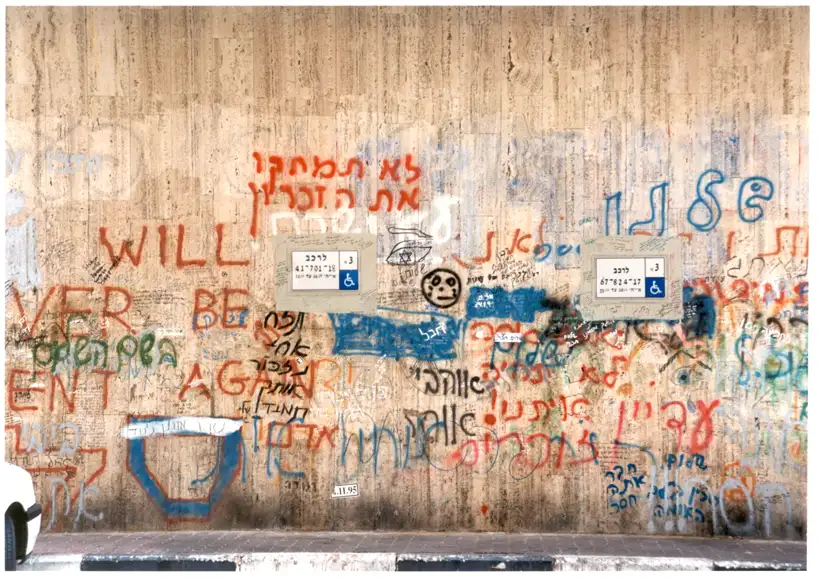

Tel Aviv – Immediately following the assassination, many Israeli citizens flowed to Kikar Malchei Yisrael. Young people and adults, religious and secular, right wing and left wing, residents of the center and residents from the periphery, veteran Israelis and new immigrants, Jews and Arabs gathered to grieve in the square. They lit candles, painted graffiti messages on the walls, sang and shed tears. In the week following the assassination, the citizens turned the square, the kikar, into Rabin Square. At the end of that week, the Tel Aviv Municipality made an official decision to change the name of the square from Kikar Malchei Yisrael to Kikar Rabin.

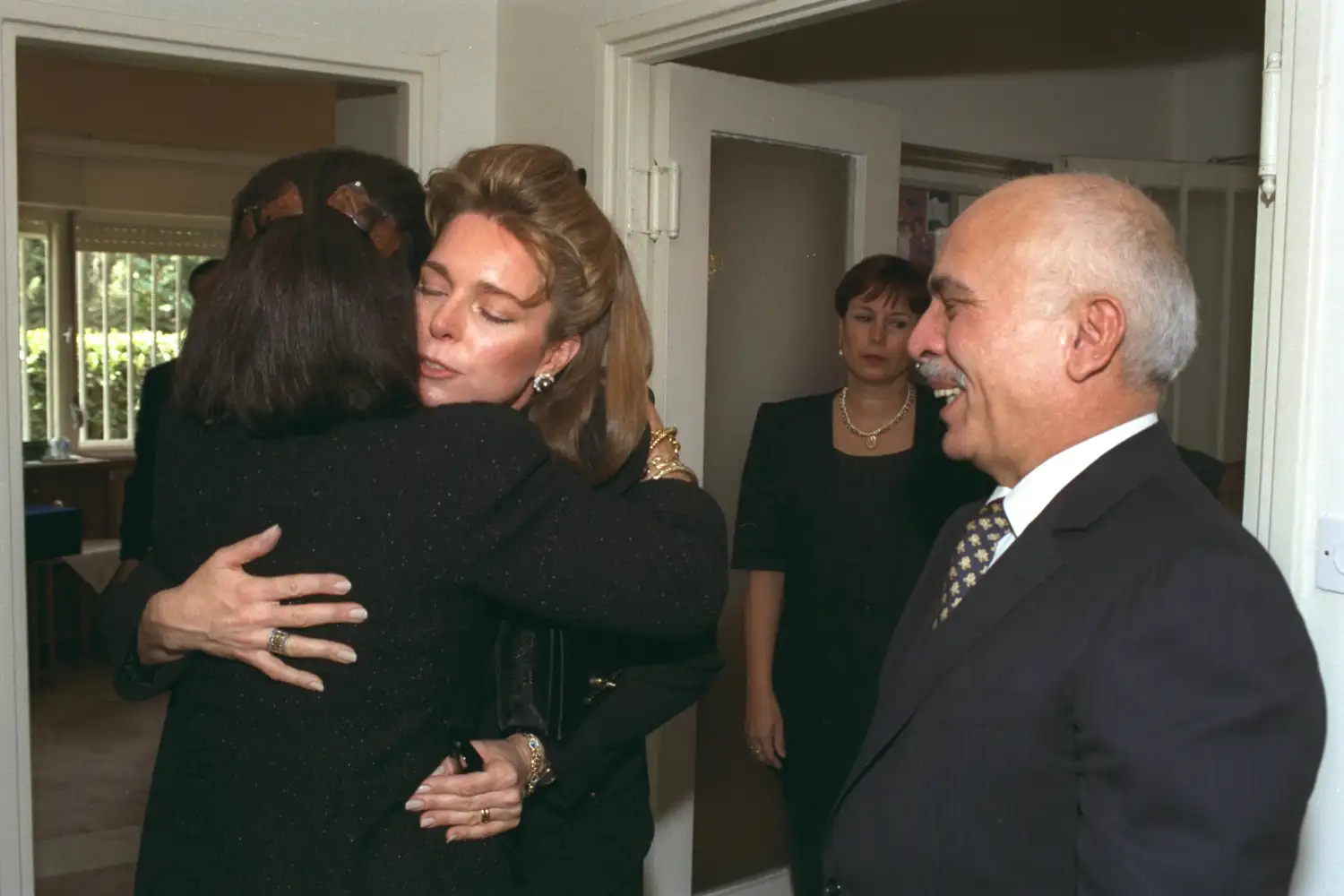

Jerusalem – Yitzhak Rabin’s casket was placed in front of the entrance to the Knesset on the day after the assassination. From Sunday morning until the funeral held on Monday afternoon, tens of thousands of citizens ascended to Jerusalem to pay their respects, walking by the casket, and saying farewell.

“Violence is the erosion of the foundations of Israeli democracy.”

Photo: Avi Ohion, Government Press Office

Photography: Dina Gona

Photography: Dina Gona

Photography: Dina Gona

Photo: Amir Gilboa

Photo: Amir Gilboa

Photo: Amir Gilboa

Photo: Avi Ohion, Government Press Office

Photo: Avi Ohion, Government Press Office.

Photo: Avi Ohion, Government Press Office

Photo: Yaakov Sa'ar, Government Press Office

Photo: Zvika Israeli, Government Press Office

Photo: Zvika Israeli, Government Press Office